Dashed expectations, a world to transform

Reflections on the experience and rejection of solidarity in the British elections.

The British elections have left many with a deep disheartening disappointment. But rather than mourn dashed expectations, I people will remember their experiences of the election campaign. On election day, Richard Seymour wrote of an experience shared by thousands:

“For those campaigning, there has been a palpable and transformative feeling of comradeship. Among the many causes for mood swings in this election, I am repeatedly struck, felled, brought to tears by unexpected solidarities and sacrifices. … It’s difficult not to believe that the country, or some part of it, is being changed for the better merely by the fact of this campaign. Or that a new country is in formation. And it’s hard not to feel a little humbled by it, as well as regretful over all one’s defensive cynicism, bitterness, point-missing intellectualism, ignorance, futile rages, pedantry, amazing opinions, and misanthropy — when, after all, this better country exists in germinal form.”

My friends who went out canvassing have shared the same experience of collective joy, mixed with frustration of occassionaly slammed doors. When I bring this up, it is not just to remember what the election result can easily lead us to forget. It is also, for what it’s worth, to share a lesson I’ve learned from following years of elections in Spain closely and spending months studying theories of interest and interest formation.

Election campaigns can — when they are energized and hopeful they may stop the enemy or even win — create a great sense of urgency and solidarity, a sense of empowerment and so a kind of materialist hope.

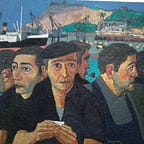

Campaigners live and embody the spirit of the policies for which they fight: solidarity, equality, transformative change. But many of the voters they meet have no such experiences. Their everyday is one of competition, resentment, or simply of non-solidarious getting-by.

So even if many of the policies of the left speak to the “material interests” of these voters, they don’t resonate with their everyday experiences and expectations, and so they seem nice perhaps, but detached from reality, abstract and utopian.

And indeed, there is no brute “material interest”, for interest is always a matter of subjective navigation, orientated by experiences and expectations, shaped by institutions and social relations, and the opportunities they thwart or afford.

These are people who, after decades of abandonment and austerity and war on working class culture and organisations, have little experience of solidarity from their fellows and the public sector. Is it any wonder many of them don’t expect solidarity, and see an expansion of the welfare state as completely unrealistic? Slogans such as “get Brexit done” and “take back control”, on the other hand, do reflect experiences of blockage and lack of control, and the expectation that a strongwill can fix it — an expectation confirmed every day by the experience of the semi-despotic power of the boss or Jobcentre-bureaucrat.

And then there are all those who share these experiences without voting for the Tories. They count a third of the electorate, and among them Labour would, no doubt, find more “natural voters” than any other party.

This clash between activists’ deep experience of solidarity, and the electorate’s cold rejection of it has left many activists in shock and mourning. Cynicism is not far away, nor is political depression. This is a time for political care.

But even if Labour had won, producing solidarity through electoral campaigns and policy promises has an important limits. Campaigns end. And they don’t suggest their own continuity. The great wave crashes and recedes from the coast of election day.

In Spain, Podemos entered the scene even more dramatically than Corbyn Labour. It went from newly born to first in election polls within a year. The reason for this rapid rise was the mass movements of 2011. They had created a constituency for a different politics, experiences of solidarity, and expectations that democracy could be used to produce a society more equal, solidarious and free.

To compete in elections, Podemos soon transformed intself into a powerful “electoral machine”. For the first elections it mobilized impressive campaigns (though the ground campaign was not as impressive as Labour’s). But election upon election (8 in the last 5 years) has worn out activists. This has weakened everyday struggles, and with it the social resonance of the left’s ideas.

Podemos mainstreamed its policies and streamlined it’s messaging. This demoblized its base, but didn’t win it a kinder treatment in the mainstream media. Labour has avoided this error and maintained a powerful and active membership. But will it remain organized and mobilized in the years to come — and how?

Many come out of the campaign transformed, ready for more, even if momentarily demoralised. And this is where the solution lies, both to the problem of demobilization, and the problem of voters’ disbelief in solidarity.

On election night on Novara, Aaron Bastani rightly criticised Paul Mason’s idea that there’s a progressive majority in the UK that needs to be represented. No, it needs to be built, he said. But (and I suppose Aaron agrees), alternative media is far from enough to do that. Solidarity must be experienced to be believed.

The solution lies in the continued production of solidarity in the everyday. The production of solidarity not just within the left, but within society more broadly. Without it, the enthusiasm of the last week will turn into nothing, and the enthusiasm of the next election campaign will run into the same cold, defeatist rejection of solidarity and hope.

In UK it likely be 5 years until the next Parliamentary election. To win it — and do much more besides — the experience of solidarity must be spread between now and then. I understand the call for self-care, self-defense and safe spaces in Brexit Britain, but there can be no tranformative politics without the continual courage to go into unsafe spaces together, which was so important to the canvassing campaign.

A first question to ask is how the non-voting third of the electorate, and the defected Labour voters who will suffer from Tory Brexit, may come to experience solidarity.

The experience of solidarity without which the left is unlikely to win, isn’t just about mutual care and togetherness, but about getting things done with people who were strangers a minute ago. It’s an experience of taking back control over ones lives, collectively, step by step.

The production of experiences and expectations of solidarity requires a strenghtening, transformation and politicisation of trade unionism and community organizing, anti-fascist work, and climate activism. For Labour, all this entails a rethink of the party’s municipal work and strategy, its engagement with unions and social movement, and the transformation of Momentum into an incubator of solidarity and struggle.

Elections happen rarely. And elections that produce a mass experience of solidarity are exceptional. The everyday happens, well, every day, and every day is an occasion to practice solidarity, which prepares the ground for struggles, and for electoral victories too.

There’s a key lesson in all this, also for people campaigning for a Green New Deal: For the most part, electoral victories for the left aren’t the means to a social transformation as much as the expression, in the field of representative politics, of a social transformation, a transformation of experiences and expectations, that is already happening.

📝 Read this story later in Journal.

🌎 Wake up every Sunday morning to the week’s most noteworthy stories in Society waiting in your inbox. Read the Noteworthy in Society newsletter.